Chapters of KOMONDOR history

“A herd around my wooden chest,

Six Komondors guard without rest,

Not afraid of bandit or beast,

I live free on the pasturing field.”MÁTYÁSI József

Komondor is one of our oldest and most characteristic dog breeds. It was probably brought to the Carpathian Basin during the Migration Period, used for guarding and accompanying herds and flocks. The breed is mentioned in sources written centuries ago. KÁKONYI Péter speaks of it in his story of King Astiagis, written in 1574:

“The shepherd saw a kamondor bitch

Feeding and encircling the child

Protecting it from beasts and birds,

Nurturing it with its own warmth.

The shepherd picked up the child from there

Starting toward the city with it,

The kamondor followed him barking

All the way to the door of his hut.”

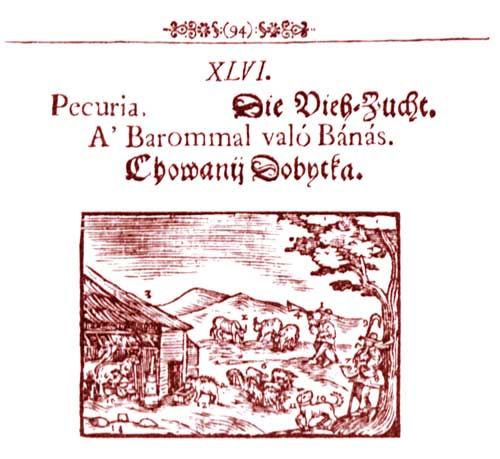

Comenius writes in his Orbis Sensualium Pictus Quadrilingvis published in 1685, in the chapter titled “Taking care of livestock”: /The numbers in the text refer to the numbers in the picture./

“The shepherd 5

pastures his flock, 6

prepared with bagpipes 7

and a bag as well as a crook 9

keeping with him

his komondor dog, 10

which is armed

(protected)

against wolves

With a spiked collar 11”

The 1724 Janua Lingva Latinae was also written by Comenius. In the chapter on herding livestock, he writes the following about the herd and the wolves:

“from whom kom ndors guard and protect them; and from whom kom ndors themselves are protected by the spiked collar around their neck.”

Rajtsits quotes BUZZI Géza Félix, a “pupil” in this subject of KOVÁSZNAY Zsigmond Sr., who bred purebred Komondors, these ancient Hungarian dogs, since 1841. The pupil, who one might say later became the one among dog breeders who studied sheepdogs most thoroughly, said:

“I followed and continue to follow in his footsteps, according to which classification our dog breeds include: the Komondor (with shaggy, or rather corded hair), the Kuvasz, in some parts commonly referred to as furry dogs that have a non-matting coat, which are also regarded as smooth-haired Komondors by some, unfortunately.”

This might be the first description that distinctly discriminates between Komondor and Kuvasz, pointing out the difference, as older texts—as we have mentioned before—are ambiguous in their description and use of names.

The development of its external features was influenced by the extreme weather conditions of the Eurasian Steppe—the scorching hot summers and exceptionally harsh winters. Its special coat structure functions as a thermostat, protecting the dog from heat and cold alike. Its hair, consisting of a coarser topcoat and a finer undercoat, does not shed—the dead hair creates the matted, ribbon or corded structure of the coat. This amazing fur is not as difficult to take care of as one might think. With careful and regular maintenance, we can prevent the cords from matting together. Thanks to its structure, the coat is self-cleaning—it will return to a beautiful ivory colour after drying, even if the dog decided to take a mud bath.

Due to their large size, Komondors grow slowly, only reaching their full size when they are about two years old, and their coat takes much longer than that to grow into its full splendor. The breed can be generally described as having powerful, resistant physique, and not sensitive to environmental conditions. The same cannot be said about its “soul”. Behind the ample fur coat of Komondors lies an even bigger heart, which sets them apart from many other large guarding dogs. The reason behind that might be that while many similar dogs were bred specifically to work independently, supervised by a single person at most, Komondors had a closer connection with their families. They were not guarding herds put to pasture in the high mountains alone, but the campsite and later the farm, where they were kept with the livestock and the family.

They do not require rigorous training in the strict sense, they naturally know everything they need to work, there is no need to demand anything else from them. It is unnecessary to train them in guarding, as that instinct is so deeply planted in them that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to take it out of them.

Just as the 19th-century song cited above tells us, herdsmen could trust their dogs with their own and their animals’ safety even in areas threatened by wolves and highwaymen. They guard their territory unyieldingly, not knowing mercy or fear. They will not let any living beings enter the area under their control—as a Komondor owner once said, “it might even catch the sparrows if only it could fly after them”. They mostly find a spot with a clear view of the whole area and lie their quietly, but sometimes they rely on the signal of other dogs, jumping in to take care of matters at the first suspicious sign. Their attack is silent and impossible to defend against: they tackle the invader like a steam engine, pushing them to the ground, and if it still dares to move, they remind it of its mistake with the strong grip of their huge jaws. That said, you do not hear anything like those unfortunate stories that keep happening nowadays, as Komondors do not aim to kill, only to incapacitate the invader. Seeing as they attack, people who do not know them might think that it could be dangerous to keep such fierce animals at home, but Komondors seem to have a kind of indestructible barrier that block any kind of aggression when it comes to their family.

That is understandable, considering how the breed’s selection happened until it reached its current state: if a dog of such size and might turns against domestic animals or people, there would be not much variation in the outcome, so probably any dog that failed to respect the rules was ruthlessly weeded out since ancient times.

Make sure to be consistent in their training, giving them a lot of love and respecting their needs. With proper care, they will really live up to the name “the king of dogs”, and remain forever loyal friends and protectors of the family.

Now let’s look at the words written by MISKOLCZI Gáspár in 1691, according to which a shepherd must:

“… always protect them with all his might, as well as with the help of his Komondors…”

So, it is established that dogs called Komondor served to guard flocks, but what did they call Komondors?

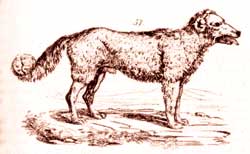

In 1846, HANÁK János uses the name “Hungarian Komondor” to describe a dog like a Kuvasz, adding a copy of the picture used a few years before in Treitschke’s book for a dog called “shaggy Hungarian sheepdog”, described with the characteristics of Komondors. (In the same book, Treitschke also gives a description of the Kuvasz, calling it “fuzzy Hungarian Sheepdog”.) Interestingly, Komondor descriptions never mention the name Kuvasz, but in descriptions of the Kuvasz, the other breed frequently comes up. Hungarian Komondor, swan, grey, sooty, red Komondor (MÉHELY 1901), smooth-head Komondor (MONOSTORI 1909), wavy-hair Komondor (KERPHELY), smooth- or wavy-hair Komondor (FÉNYES Dezső).

Descriptions of the two breeds tend to change chaotically over time with every author. Sometimes long-hair Komondors are smaller and those with shorter, non-matting hair are larger, and sometimes it is the other way around. It actually makes sense if we consider that researchers have evidently seen Komondors whose hair was cut short when the sheep were sheered, or which “shed to pants” (lost their hair on their neck, chest and front legs) after whelping. One thing is certain: dogs other than white were seen as mixed breeds even back then.

In 1914, BUZZI Géza Félix used pictures in “Nature” magazine to present Kuvasz and Komondor, which are starting to resemble how we describe these breeds today.

As we could see, the names used today were created as a result of the classification done at the beginning of the 20th century, so we can say that the breed names used in descriptions written before that do not necessarily refer to the breeds we would mean by them today. For example, it is common to see names such as grey, red, sooty Komondors, which certainly do not refer to the breed we call Komondor today, but some other, probably mixed breed dog used for guarding or herding, of which there are still many out there.

Breeds recognised today—as we have mentioned—are a result of targeted breeding, as a clear distinction between the various types was only made in 20th-century professional breeding.

Despite that, it still happens with livestock guardian breeds that purebred parents produce whelps resembling the other breed more—of course, such dogs are excluded from further breeding. But in case of the Kuvasz and Komondor, this phenomenon is unheard of.

(ÁRKOSI József – Magyar Pásztorkutyák (Hungarian Sheepdogs) – Alexandra Kiadó)